For D.C. Artists, A Dark Period For D.C. Artists, A Dark Period By David Montgomery By David Montgomery

Washington Post Staff Writer

Thursday, May 18, 2000; Page B01

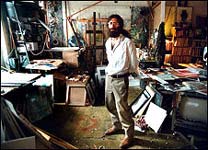

Michael Berman's light-drenched studio used to be filled with his fiery abstract images, but now the walls also display much different work: old buildings, rendered in haunting colors and lines that seem to communicate ache and doom.

This is what comes of working within century-old walls slated to be demolished for a $50 million office building.

A familiar Washington struggle is playing out in the 900 block of F Street NW, a street that used to be the city's main shopping artery. Today it features vacant storefronts beside bargain outlets that are still open but badly in need of repair. The contest pits artists and preservationists against developers, with the city leaning in favor of the developers.

This time the battle carries extra poignancy. At stake is the last intact block showcasing the three-story 19th century commercial structures whose architecture once dominated downtown. And the dozen art studios above the storefronts are among the last in the so-called Downtown Arts District, created in part to keep artists from moving out or being driven out.

"We're all wondering what happened to that," Berman said. "When we go, that's it."

The block is critical to downtown's economic revitalization, according to city planners. To the east are the Portrait Gallery, MCI Center and the booming development around Seventh Street NW.

The show is called "Salon des Ejectes," and it includes Berman's work "F Street Lament," depicting the 19th century facades seemingly dripping blood.

To the west are the old Woodward & Lothrop building, poised for redevelopment, and the more established sections of downtown. The office building that would supplant the period architecture would have shops on the first floor.

"This project, as well as the Woodies project, is critical to the renaissance of F Street as a major retail shopping destination," said Tom Wilbur, senior vice president of the John Akridge Cos., which is planning the office building.

The landlord is the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Washington, which would use the proceeds to enhance the work of Catholic Charities and to support the adjacent St. Patrick's Church, itself a historic landmark.The preservationists would prefer a smaller-scale project that would restore the buildings and save the artists. So would the artists. Both groups have sued to block city demolition permits. Seeking compromise, they met this week with Akridge representatives to discuss a smaller building.

But bracing for the worst, the artists are presenting a last hurrah tonight. It is the opening reception of a new show of their work at the 505 Gallery on Seventh Street NW. The show is called "Salon des Ejectes," and it includes Berman's work "F Street Lament," depicting the 19th century facades seemingly dripping blood.

Just six months ago, the artists were in a much more celebratory mood. They had scored what they thought was a major victory to stop the project. Then things turned a little strange.

The archdiocese's plan was to demolish 11 buildings on the block, restoring the three-story facades of the seven most historic ones, and to erect an 11-story office building behind the facades. It also proposed to renovate and expand nearby Carroll Hall.

Seven of the buildings are deemed by the city as contributing to the Downtown Historic District. The archdiocese argued at a city hearing that restoring the facades was a key benefit of the project. It also asserted that the project had "special merit" for a number of reasons, including the expansion of Catholic Charities and the relocation of some of its offices to the neighborhood.

But Administrative Law Judge Rohulamin Quander, acting as the Mayor's Agent for Historic Preservation, ruled Nov. 9 that the project did not possess the required "special merit" to justify demolishing all but the facades of the seven historic buildings.

It seemed like a big win for the opponents of the project--but for a pesky detail.

"The city has a historic district and an arts district. Why aren't they defending their own law?"

Quander acknowledged in his ruling that he was issuing it two months after the 60-day deadline that city law required him to meet. Quander explained that he had been busy as acting chief judge, with limited staff.Based on this technicality, the archdiocese appealed Quander's ruling. Before the appeal could be heard, the D.C. Department of Consumer and Regulatory Affairs issued demolition permits, overruling Quander.

"The fact that this city doesn't care and keeps on letting things get destroyed is such a sin," Berman said. "The city has a historic district and an arts district. Why aren't they defending their own law?"

Lloyd Jordan, director of Consumer and Regulatory Affairs, said the department issued the permits after the corporation counsel's office advised that the missed deadline voided Quander's ruling. But he emphasized that the developer still must get other permits before proceeding.

In their D.C. Superior Court lawsuit to block the demolition, the Downtown Artists Coalition, the D.C. Preservation League and the Committee of 100 on the Federal City say the permits were issued in violation of city law.

In the meantime, Akridge's Wilbur hopes the meetings between the developer and the preservationists and artists may resolve differences. He said the archdiocese will accept a smaller building.

But Sally Berk, who testified before Quander as an expert in preservation, said the developer is offering to eliminate only two stories from the building. "It's still a nine-story office building with facades pasted on the front," she said.

Up in the artist studios--with their big windows, high tin ceilings and affordable rents--painter Judy Jashinsky just embarked on several large canvases. The looming demolition will be incentive to work quickly, she joked. And she said she would not be able to afford such ample wall space in her next studio if she is evicted.

Most of the artists have work for sale in the "Salon des Ejectes," Berman said. If the negotiations and lawsuit fail, a portion of the proceeds will go toward moving expenses.

© 2000 The Washington Post Company

Top

Back to News |