The following article is Copyright by Nigel Tranter. All rights reserved.

Reprinted by permission of the Nigel Tranter Estate

A Letter from Arbroath

By NIGEL TRANTER

The following article was written in early 1970 when Scotland was about to celebrate the 650th anniversary of a critical moment in her fortunes. That moment occurred when a group of men gathered at Arbroath to compile a letter to the Pope - - the Declaration of Arbroath. NIGEL TRANTER sees in this noble document a message for Scots of 34 years ago before Devolutiion and, I'm quite sure, for today as well. It is also of vital importance for the people of all nations who prize freedom and it is essential for the understanding of the significance of Tartan Day which we celebrate each year on 6 April. Rory Mor, Editor

ONE might be forgiven for wondering whether there was ever another race quite like the Scots, another nation so continually in a ferment, so consistently divided against itself, yet so thirled to, and concerned for, its historical if not its actual and political integrity. Surely only in Scotland could a people be preparing to celebrate the 650th anniversary of its most renowned national proclamation and statement of faith, with much pride and acclaim; yet find themselves little further, if as far, along the road to the goal and objective so splendidly set forth in that declaration all those centuries before and be, in the main, so blandly unaware of any discrepancy.

Nowhere else, I think, could the word, the spoken, sung and declared word, be so venerated, the spirit vaunted, and the practical application thereof almost utterly ignored. Are we a race of hypocrites, then? I sometimes fear that we are. Perhaps not more so than other races and peoples who delude themselves; the Germans, with their Wagnerian sentimentality; the Italians with their desperate virility, the French, with their alleged worldly-wisdom; the English with their island-race-of-seamen illusion. But the Scots chose freedom for their national preoccupation. And freedom demands more than just singing about it. Moreover freedom is susceptible to test, others can all too readily judge whether our devotion to freedom is all that genuine!

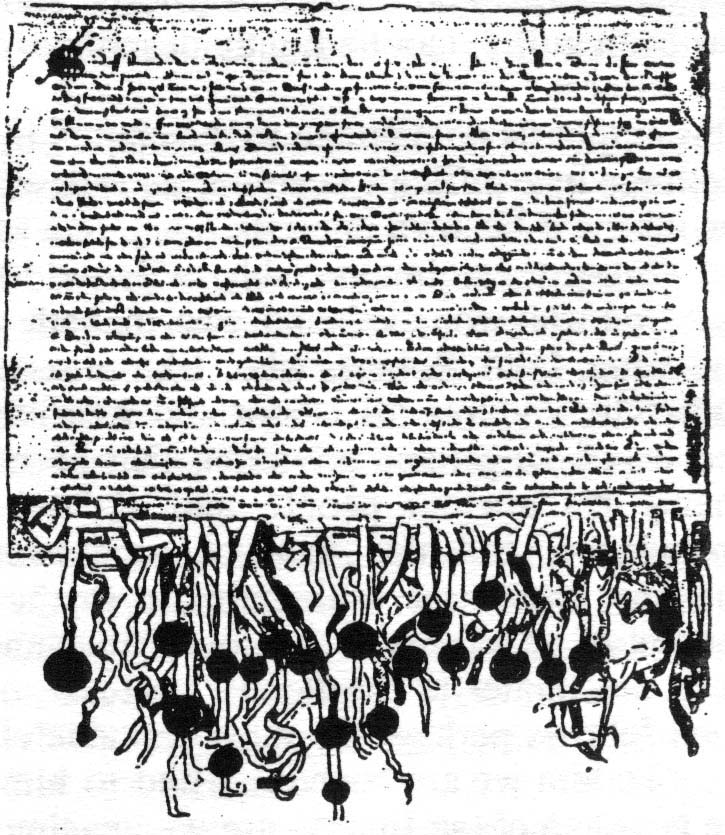

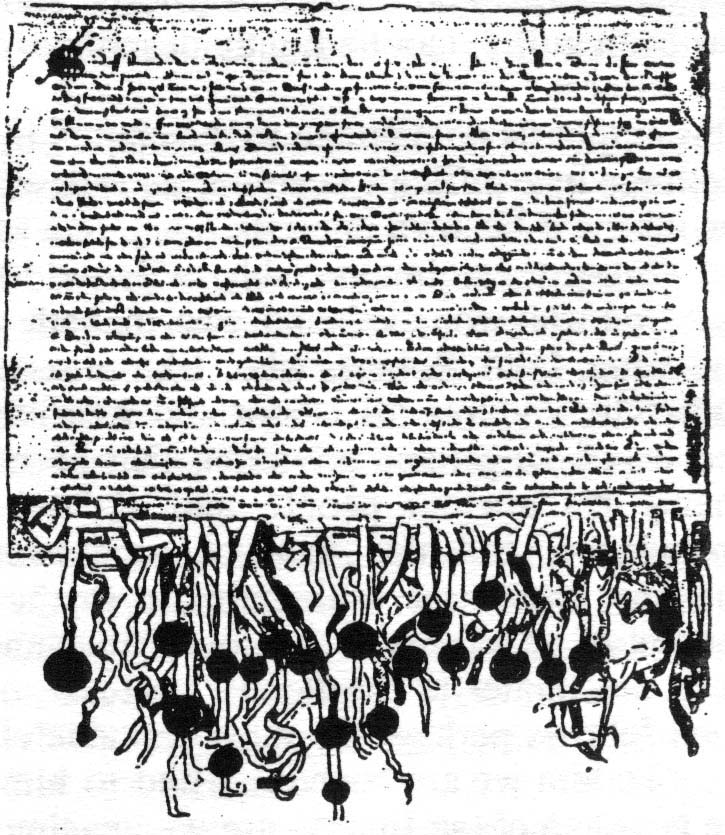

The famous Declaration of Arbroath was drawn up and signed on April 6, 1320, six years after Bannockburn, in the fourteenth year of Robert the Bruce's embattled reign, all nine years before his death. It so happens that I am at present writing the last volume of a trilogy of novels dealing with the life and times of The Bruce; and this matter of the Declaration of Independence inevitably comes prominently into my considerations and my writing.

As we start this year of 1970, I feel that it is our simple duty to consider for a little the events, pressures and lessons of 650 years ago, when we as a people more or less started on the long, long road towards national freedom -- consider and ponder. There had been an independent Scotland for centuries before that, of course; but its independence and entity had not been really threatened. Therefore the conception of national freedom had hardly come up.

Some understanding of the background and circumstances against which this Declaration was compiled, and the personalities involved is necessary for full appreciation. For exactly thirty years Scotland had been struggling to maintain her national independence and identity, in the face of almost overwhelming English assault and dominion; for twenty-four of those years by armed resistance. And in the process had lost appallingly in lives, progress and wealth. But had gained also, by the sorest means known to a people, in two vital concomitants of nationhood -- unity, and a passionate devotion to freedom.

Edward the First, King of England, was well-named 'the Hammer of the Scots', for he it was who hammered and forged these two essential ingredients of nationality upon the Scots people, by his lust for power and his pathological hatred. For it must be remembered that, prior to Edward 'Longshanks' hammering, Scotland, although claiming perhaps the most ancient royal line in Christendom, had had little sense of nationhood; and freedom, national freedom, was something that had hardly arisen, in that it had not been endangered.

The Situation That Existed

It is difficult, today, to visualise the conditions that prevailed prior to Edward's aggression, political and military, used as we are to the ScottishEnglish dichotomy, the Auld Enemy idea, and a dearly defined national entity. Until 1290 Scotland and England were normally good neighbours, and the border between them fluctuated and was indeed of little practical importance.

There was then enormous coming-and-going between the two realms in Church and in State, land ownership and personal relations. The ruling classes of the two kingdom were almost inextricably mixed partly as a result of David the Firsts policies and Anglophile attitudes and partly as a natural outcome of the dominant Norman-French knightly prowess and tradition. Many great lords would have been hard put to it to tell whether they were in fact Scots or English, if they ever really thought about it, including The Bruce himself, until he made his dramatic choice. Much of the nobility of both realms owned as great estates in one land as the other; the kings of Scots held lands in England also - a significant matter; hereafter; and churchmen of both countries held office in the other.

Although entirely relevant, it is not for me here to describe how and why all this came to be changed by Edward the Angevin's savage ambition, allied to the grievous accident that left Scotland kingless when Alexander the Third fell over Kinghorn's cliff in 1286. Suffice it to say that Edward thereupon claimed suzerainty over Scotland, because he said Alexander, had done homage to him, by proxy, for his English lordship of Tynedale, and because he, Edward, had been chosen to act arbitrator in the competition for the vacant Scots throne, appointing thereto the weak John Baliol as nearest heir, against the claims of Robert the Bruce's grandfather. And when his puppet, Baliol, driven to desperation, at last refused to dance further to Edward's string-pulling, he drew the sword with which he was so expert, the first Knight of Christendom, and the bloody Wars of Independence were started.

Of the utterly appalling savagery, the untold suffering, the desolation and desperation of those decades of wholesale bloodshed, treachery and hate, as well as of blinding heroism and dauntless courage, we cannot deal here. We must forbear to expiate on William Wallace, the first Scotsman ready to perceive the meaning of disinterested patriotism and the greatest, truest hero of our history. And to take for granted the rise of Bruce, from being a very doubtful hero indeed to the pinnacle of the hero- king whose fame has resounded around he earth ever since.

We must pass over the dire days, months, years when Scotland lay prostrate, harried, bludgeoned, battered, tortured and starved beneath the mailed heel of the greatest soldier and fiercest tyrant of his age, and only the tiny flicker of faith in one man's heart saved this ancient realm from entire extinction - a faith which commenced only as a belief in his destiny but developed into the burning faith in a people's freedom. All this we must take as read, and accept only Robert Bruce's eventual profound dedication to the freedom which in twenty-four searing years he fashioned and brought to perfection and acceptance.

A Letter to the Pope in Rome

Because it is against this backcloth that the Declaration of Arbroath was written -- and not by Robert Bruce, although not one word therein could have been written without him. This is what makes the reference to Bruce therein so startling, so utterly electrifying, and so poignant. Only when this is understood can the full meaning and vision of the Declaration be recognised.

Many of us, I know, fail to realise that in 1320, six years after the success of Bannockburn, Scotland was still fighting for her independence. The English had been trounced in that momentous battle, yes -but they were not thereby brought low and humbled, or changed one iota in their ambitions. They merely changed the direction and tempo of their assault. What produced the need for this Declaration was the fact that they had brought the Pope, John the 22nd, in on their side. This was not new of course, for, though the Church in Scotland itself had all along been Bruce's most faithful support, Holy Church as represented by the Holy See had always been against him -- the excommunicate murderer of John Comyn.

But, at this stage, the Pope's fulminations and anathemas against Bruce and his kingdom were particularly strong and menacing -- to the glee of England. The Pope indeed refused to recognise Bruce as king at all, and censured him as a usurper, addressing him by letter, and sending his legates only as to Robert Bruce, Governor of the Kingdom of Scotland. This papal attitude allowed Edward the Second to refuse piously to make the peace treaty Scotland so greatly required, for its security, well-being and advancement. Moreover, it put the Church in Scotland in a very awkward position.

So it was decided to send a letter to the Pope, not from Bruce himself, but from the whole community. Indeed, the Declaration is endorsed thus:

"A letter addressed to the Lord Supreme Pontiff by the community of Scotland"

A community cannot write a letter, and, although it was sealed and assented to by a great number of the leaders of the people and officers of state, it yet had to be composed mainly by one hand. And that hand almost certainly belonged to Bernard de Linton, Abbot of Arbroath. De Linton's career was a meteoric one. A young parish priest of no known lofty connections, he was merely Vicar of Mordington, an unimportant though strategically placed parish just north and west of Berwick-on-Tweed, when he was brought to Bruce's notice. How this came about we do not know, but it happened during that period when the king had returned from his Hebridean exile and was engaged in the enormous and daunting task of winning back Scotland fight by fight, castle by castle, village by village, from an overwhelmingly superior and well-organised occupation force, a time of shocking peril and recurrent disaster, when only the very stoutest hearts would rally to his tattered banner, with hanging, drawing and quartering the well-advertised fate of all who fell alive into Edward's hands. So Bernard must have been a brave man, whatever else, and no mere wordspinner.

There might be a clue to his coming to Bruce in the fact that Lamberton is just over the hill from Mordington. And William Lamberton, Bishop of St. Andrews, principal cleric of Scotland and Bruce's great friend and supporter, was at this time a captive in England. But a rather curious captive, in that he was allowed a great deal of freedom for reasons too involved to go into here. He was permitted to travel about the North of England, so long as he did not cross back into Scotland -- presumably having given his parole.

At any rate, he proved an excellent source of information for Bruce on English movements and affairs -- a sort of ecclesiastical fifth column; and with Mordington plumb on the borderline and the Tweed, but outside the populous and dangerous Berwick area. What more natural than that he should use the young and active vicar, whom he probably would know personally, as go-between? We can visualise many a night-time row across Tweed in a salmon-coble, between the young cleric and the old, and long journeys in search of the elusive Bruce thereafter.

This is the merest supposition, of course. But however he was introduced to the warrior-king in hiding, this unknown and otherwise untried young priest was made secretary and chaplain to the monarch, and in a comparatively short time promoted to the almost princely mitred abbacy of Arbroath -- this partly as a device to get rid of the incumbent abbot, who was pro-Comyn and pro-English; and partly as bestowing on him a high enough rank so that he might be made Chancellor, or first minister of state, without too greatly offending other eligible clerics.

All this, of course, was before Bannockburn and the fruits of victory, when such appointments actually began to mean something. At that great battle, Abbot Bernard bore before his master into the thick of the fray the famous Brecbennoch of St. Columba, now better-known as the Monymusk Reliquary. Obviously he was a man of deeds and great courage.

But it is his words which especially concern us here. We believe for various reasons that be was the real composer of the Declaration. Firstly, it was dated and sent from Arbroath Abbey. Secondly, only someone in a position such as the Chancellor's would be able to obtain all the illustrious assents and sealings -- not signatures, it is to be noted. Thirdly, the Latin in which it is written is very stylised, and that in a style which compares exactly with other writings of Abbot Bernard, concise, admirable, stirring. Also, it was clearly the work of a cleric, from the subject matter and from its destination to the Pope.

There is a lot more to the wording of the letter than meets the eye -- even after this brief historical background-sketch is taken into account. There is also a great deal to be learned from the seals and assents attached, which is not obvious at first glance. For one thing, no bishops or abbots are included. Considering that these were amongst the most valiant fighters in the long struggle, this might seem odd. But the fact was that most of them were at the time persona non grata at the Vatican, refusing summonses to Rome, some actually excommunicated, like Bruce himself; and their signatures could have been construed as invalidating the document, providing the Pontiff with an excuse to reject it allegedly unread. Moreover, the clerics had already submitted a manifesto of a similar type, from Dundee, in 1309.

More interesting are some of the names of Earls, barons and knights chosen to subscribe this Declaration. Most of them were veteran supporters of the fight for liberty, such as Randolph, Earl of Moray, the King's nephew; Malcolm, Earl of Lennox, his old friend; Walter the High Steward, his son- in-law; the Good Sir James Douglas, his dearest companion-in-arms; and Sir Gilbert Hay, the High Constable. There were others, though, who were highly-placed traitors, back-sliders whose records were quite deplorable, or men who had been all along on the English and Comyn side.

Such were the Earls of Fife, Dunbar and Strathearn; Sir Ingram de Urnfraville, brother of the Earl of Angus, Sir David de Brechin, Sir John Stewart of Menteith; Sir Roger de Moubray; and Sir William de Soulis. Brechin, Moubray and Soulis, indeed, were all convicted of treason that same year. Almost certainly these men were asked to subscribe as both a test of their repentance and a check and pressure for future better behaviour.

Such were the Earls of Fife, Dunbar and Strathearn; Sir Ingram de Urnfraville, brother of the Earl of Angus, Sir David de Brechin, Sir John Stewart of Menteith; Sir Roger de Moubray; and Sir William de Soulis. Brechin, Moubray and Soulis, indeed, were all convicted of treason that same year. Almost certainly these men were asked to subscribe as both a test of their repentance and a check and pressure for future better behaviour.

It must not be forgotten how great a part of Bruce's task and success was the uniting of his sorely divided kingdom, both during and after the warfare; and how extraordinarily generous and forgiving he was towards the innumerable traitors -- much against the wishes of many of his closest lieutenants. All with this goal of unity. This is often overlooked, and was one of the King's greatest achievements -- for he was by nature a man of strong views, violent passions and no half-measures.

As to the wording, there are, of course, certain slightly varying translations of the Latin original. It is a lengthy document, and too long to quote in full here. But certain sections are very significant. After the superscription, there is a long preamble, summarising the age-old history of Scotland, from misty and semi legendary beginnings, right down to the end of the 13th century -- this to emphasise to the Pope that Scotland had always been an independent country, with no overlordship from England or elsewhere -- and an indication of the 113 kings, however fabulous, to reinforce the message. Then comes:

"Under such free protection did we live, until Edward King of England . . . covering his hostile designs under the specious disguise of friendship and alliance, made an invasion of our country at the moment when it was without a king, and attacked an honest and unsuspicious people, then but little experienced in war.

The insults which this prince has heaped upon us, the slaughters and devastations . . . his imprisonments of prelates, his burning of monasteries, his spoilations and murder of priests, and the other enormities of which he has been guilty, can be rightly described, or even conceived, by none but an eye-witness."

This emphasis on damage to the church in especial, is, of course, to put His Holiness in a difficult position, as one who has backed the wrong horse, to the injury of his own interests.

"From these innumerable evils we have been freed, under the help of that God who woundeth and who maketh whole, by our most valiant Prince and King, Lord Robert, who, like a second Maccabaeus, or Joshua, hath cheerfully endured all labour and weariness and exposed himself to every species of danger and privation, that he might rescue from the hands of the enemy his ancient people and rightful inheritance, whom also Divine Providence, and the right of succession according to those laws and customs, which we will maintain to the death, as well as the common consent of us all, have made our Prince and King."

This, as counter to the Pontiff's refusal to recognise Bruce's true kingship. Then follows perhaps the most dramatic clause:

"To him we are bound . . . and to him as the saviour of our people and the guardian of our liberty, are we unanimously determined to adhere; but if he should desist from what he has begun, and should show an inclination to subject us or our kingdom to the King of England . . . then we declare that we will use our utmost effort to expel him from the throne, as our enemy and the subverter of his own and of our right, and we will choose another king to rule over us, who will be able to defend us; for as long as a hundred Scotsmen are left alive, we will never be subject to the dominion of England. It is not for glory, riches or honours that we fight, but for that liberty which no good man will consent to lose but with his life."

Most Extraordinary Statements

This, of course, by any standards, is quite one of the most extraordinary statements, considered, endorsed and published, of all time. We are apt to be so familiar with it now, that we probably tend to overlook just how revolutionary and outstanding it is. Consider for a moment what is stated and implied. Robert the Bruce was the greatest hero of his age, the greatest fighter for freedom, the beloved leader of his people, the most popular King Scotland had ever had. Yet here was a public announcement of his principal subjects and closest associates, declaring to the world that they would reject, abandon and expel even him if he did not continue to measure up to the lofty standards of liberty and freedom now set forth. Moreover, this was the age of absolute kingship, royal dictatorship if you like, when monarchs ruled by divine right as well as by the power of the sword. But here is a people proclaiming to him, as to all others, that they will unseat him and choose another to rule over them should he fail in this essential respect for freedom.

Here above all, is proudest democracy, a valiant profession of a conception at the period almost unheard of amongst the nations of Christendom, an astonishing foretaste of the spirit which was to animate the Scots down the coming centuries, however many the setbacks. Undoubtedly the influence of the slaughtered Wallace was behind this -- but so was Bruce's own. Although he could not sign this letter, in the circumstances equally certainly it could not have been composed and sent without his fullest assent and co-operation.

Here then is something for Scots to ponder over. And especially today, when, in the resurgent tide of national consciousness, loud voices may here and there seek to lay down dictates and make patriotism exclusive to a few. Highly interesting also is the next clause, where the compilers declare that they are prepared to do everything for peace which does not compromise the freedom of their constitution and government; and urge the Pope to procure the peace and supremacy of Christendom through a united crusade against the Infidel in Spain and the Holy Land, in which they and their King would take part with joyful hearts.

'This, of course, was a very real preoccupation in the Middle Ages, and very much on Bruce's own mind - hence his famous command, when he was dying for his friend James Douglas to take the heart out of his dead body and lead a crusade, with it in the forefront, to honour a vow he had made when his cause was darkest, and which his prolonged struggle at home had prevented him from carrying out. But, as well as being a true and popular challenge to the Pontiff, this was also a very subtle move, since all the rulers of Christendom were in theory committed to the task of expelling the Infidel, and the Pope most of all.

This was a demand which he would find it very difficult to ignore or play down. And much to the point is the delightful postscript, to the effect that if the King of England would leave them in peace, he would not himself be able to plead, as an impediment to going crusading, his wars with his neighbours.

We Commit the Defence of Our Cause To God

The ending of the Declaration is possibly the most essentially dramatic of all, since it all but puts the Holy Father on trial before God, a boldness almost unheard of in those days.

"If Your Holiness do not sincerely believe these things, giving to implicit faith to the tales of the English, and all this ground shall not cease to favour them in their designs for our destruction, be well assured that the Almighty will impute to you that loss of life, that destruction of human souls, and all those various calamities which will follow. Confident that we now are, and shall ever as in duty bound, remain obedient sons to you, as God's viceregent, we commit the defence of our cause to God, as the great King and Judge, placing our confidence in Him, and in the firm hope that He will endow us with strength, and confound our enemies; and may the Almighty long preserve Your Holiness in health . . ."

Such then is the renowned Declaration of Arbroath, a writing of which Scotland has every reason to be proud, a document infinitely more significant and splendid than the Magna Carta, which our friends in the south admire so greatly, but which was concerned with the rights of property, and barons' property at that.

Whatever the small differences of expression produced by various translators of the Declaration, the general tenor and message is the same. Let us remember that it was composed after long and agonising years of the most savage oppression and diabolical cruelty. And that it was necessary that the Pope should learn, without any doubt, that his policy of supporting England against Scotland was not only repellent but pointless.

If it is suggested that such conditions and reactions have little relevance to the present day, let us not forget Czechoslovakia, Tibet, Biafra, and other places, and the situation of many minorities inside 'respectable' states much nearer home. The lesson for us in Scotland, surely, apart from the obvious one of the need for the unending struggle for personal and national freedom, is the same need for unity of purpose at home, which was the background and preoccupation of this Declaration.

Scotland's fatal weakness has always been -- and Wallace, and later Bruce, both sought to counter it -- a preference for hair-splitting and squabbling amongst ourselves, forgetting the great objectives in the means thereto. If our celebration and consideration of the Declaration of Independence anniversary helps to bring home to us this all-important lesson, in this period of especial opportunity, with watchfulness for the dangers and pitfalls to our freedom from within, even more than from without, then our forefathers of six-and-a-half centuries ago may perhaps rest the more peaceably.

Check out another Web Site devoted to Scotland's finest historical author

Nigel Tranter 1909-2000 -- A Celebration of his life and work

Return to the Main Menu Page

Such were the Earls of Fife, Dunbar and Strathearn; Sir Ingram de Urnfraville, brother of the Earl of Angus, Sir David de Brechin, Sir John Stewart of Menteith; Sir Roger de Moubray; and Sir William de Soulis. Brechin, Moubray and Soulis, indeed, were all convicted of treason that same year. Almost certainly these men were asked to subscribe as both a test of their repentance and a check and pressure for future better behaviour.

Such were the Earls of Fife, Dunbar and Strathearn; Sir Ingram de Urnfraville, brother of the Earl of Angus, Sir David de Brechin, Sir John Stewart of Menteith; Sir Roger de Moubray; and Sir William de Soulis. Brechin, Moubray and Soulis, indeed, were all convicted of treason that same year. Almost certainly these men were asked to subscribe as both a test of their repentance and a check and pressure for future better behaviour.