By

Rob Buhrman

By

Rob BuhrmanHistory of a Self-Taught R/C Pilot / Modeler

By

Rob Buhrman

By

Rob Buhrman

I

was born in 1955. Ever since childhood, I’ve been fascinated by airplanes.

I notice every plane that flies over me, and marvel at our ability to

fly.

I

the late 1980’s, I became very interested in the people who invented powered

human flight, Wilbur and Orville Wright. My

wife and I visited Kitty Hawk, and I was thrilled to stand on the spot where it

all began in 1903. I read books on

their work, including their own journals and letters detailing how they

designed, refined, built, tested, and flew their own aircraft.

That

was when I discovered Radio Control Modeling.

I realized that I too, could build and fly my own aircraft!

So I went right down to my local hobby shop, asked a few questions, and

picked out a Goldberg Eagle 63 kit, OS Max .40 engine, and Futaba Attack 4 AM

radio system.

In the spirit of the Wright Brothers, I decided to teach myself how to fly. I figured if they could do it, I should at least be able to teach myself, since it has all been laid out for me by others. An airworthy airplane has been designed and kitted for me. A powerful, lightweight, reliable engine has been built for me, along with a very efficient propeller. A state-of-the-art radio control/servo system is ready to go, all I have to do is install it and plug in the connections. The challenge would be to put it all together properly, and then to learn to fly it without destroying the whole thing beyond repair.

I

understood the principles of flight. I

had “flown” Microsoft Flight Simulator for years, starting with Version 1.

(on a Commodore 64 computer!)

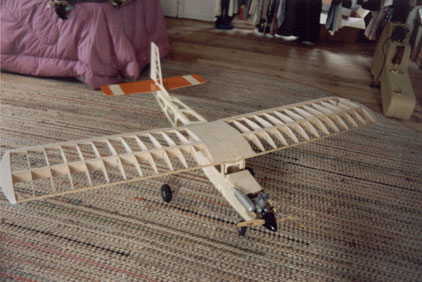

Building

the plane was fun and easy. (I was an avid plastic model builder as a kid and

the Goldberg kit and instructions were excellent for a beginner)

I followed the instructions carefully, and made sure everything was solid

and strong. I took care with the

control surface / servo / pushrod connections and carefully installed and tested

the radio system and associated wiring and electronic connectors.

I realized that everything must be correct and solid with no “weak

links”. I double-checked that the

control surfaces moved as they should, corresponding to transmitter stick

movement.

Building

the plane was fun and easy. (I was an avid plastic model builder as a kid and

the Goldberg kit and instructions were excellent for a beginner)

I followed the instructions carefully, and made sure everything was solid

and strong. I took care with the

control surface / servo / pushrod connections and carefully installed and tested

the radio system and associated wiring and electronic connectors.

I realized that everything must be correct and solid with no “weak

links”. I double-checked that the

control surfaces moved as they should, corresponding to transmitter stick

movement.

I

built a hardwood test stand for the engine and performed engine break-in.

I started my engine by hand, fueled with a rubber bulb, and used a nicad

glow starter.

During

this time, I joined the AMA, mainly for the insurance coverage.

I

took the plane to a local high school field, which was suitable for flying.

It’s big…almost 400 yards long and about 150 yards wide, with the

prevailing wind blowing the long way. The

school field is surrounded by trees and farms, without a house in sight.

(By the way, I don’t fly if there are people around).

I

took the plane to a local high school field, which was suitable for flying.

It’s big…almost 400 yards long and about 150 yards wide, with the

prevailing wind blowing the long way. The

school field is surrounded by trees and farms, without a house in sight.

(By the way, I don’t fly if there are people around).

After

some taxiing and short “hops”, I decided the conditions were right to try my

first flight. My plan was to take off, fly straight away, gain some

altitude, then cut power and land at the far end of the field. The mild breeze was blowing toward the school, which was

perfect…I could take off in the other direction, towards the trees 400 yards

away. That would give me a long

distance to fly and land.

In

a few seconds, I would find out how short 400 yards really is.

The

plane lifted off beautifully. I had

no problem keeping the wings level. I

was flying! The problem was, I was

flying higher and higher very quickly! By

the time I got over the thrill and adrenaline of watching that plane rise into

the sky, It had risen about 300 feet. This

whole process only took about 4 or 5 seconds.

I regained my sense and cut the throttle to idle, but by then I had used

up more than half of my 400 yards, and I was very high up in the air.

I stuck to my plan to not turn, and glided down as quickly as possible,

but ran out of field and “landed”. From

that far away, I could only see that the plane was stopped, but that it was not

on the ground. That’s not usually

a good sign. It was in some

(luckily) baby trees at the end of the field about 10 feet up.

The

crash just broke a couple of wing ribs and poked some holes in the covering, but

other than that, the plane was fine. Not

bad for my first attempt. I would

do much worse things to that plane in future flights.

I

should say right here that flight simulators, although very helpful and fun,

cannot make you into an r/c pilot. Something

is missing from the simulation. Controlling

an r/c plane in the air is a highly dynamic situation.

Things happen very fast, and there is little, if any, room for error or

hesitation. To be fair, I must

admit that I have not flown r/c specific simulations, and I’m sure they have

advantages in teaching the r/c pilot. But

even so, no simulator can duplicate the flying experience.

The

Goldberg Eagle 63 served me very well as a trainer.

I never lost my passion for r/c flight and modeling.

While walking that 400 yards to my plane after that first flight, I was

full of the excitement and adrenaline that comes with flying, but I was also

going over what had just happened and analyzing the flight…what had gone right

and what had gone wrong. It

wasn’t hard to figure this one out. I

had not counted on the high amount of lift and quick rise time of my craft.

The fact that I was taking off into a nice little breeze naturally

increased this lift. I also

realized that I had been slow to see the problem developing by about 2 seconds,

which was the difference between landing on the field and landing in the trees.

Over

the next few months, I flew whenever I could, always at the same field.

I learned how to turn, (kind of important) circle the field, and land,

sometimes with power and sometimes without.

I did not know enough about my engine to set it up so that it was totally

reliable, but it served it’s purpose. The

plane spent plenty of time on the workbench for repair, and I learned how to

make repairs that were strong and straight, so that I could go back to the

flying field with it.

One

time I got disoriented and lost control of my plane over some very tall trees.

I found it lodged 75 feet up in the tree.

Climbing that high in a tree is not really my thing, so the next day I

hired a tree expert to retrieve it for me.

Even though I had to pay him $40, the engine and radio system were worth

a lot more than that to me. But by

that time, my 1st plane was reaching the end of its useful life.

By

the time I retired my Goldberg Eagle 63, I was a fairly competent r/c schoolyard

flyer. I was ready for my next

plane.

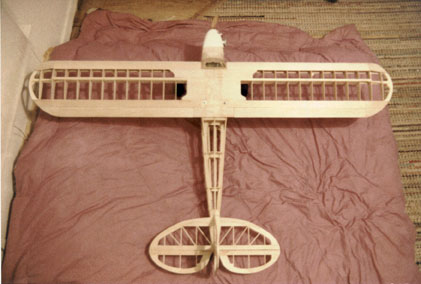

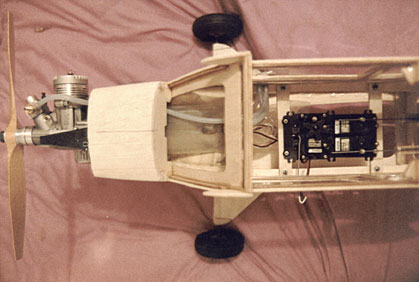

I

spent a whole winter building my Goldberg Anniversary Cub.

Although I was able to use the same radio system and servos, the O.S. .40

wasn’t enough engine for this plane, (and was pretty worn out by this time) so

I bought a beautiful Rossi .40 and installed it in the Cub.

This engine was almost twice the size and weight of the O.S. .40, and it

ran like a Swiss watch. You could

almost just breath on it and it would start.

I

spent a whole winter building my Goldberg Anniversary Cub.

Although I was able to use the same radio system and servos, the O.S. .40

wasn’t enough engine for this plane, (and was pretty worn out by this time) so

I bought a beautiful Rossi .40 and installed it in the Cub.

This engine was almost twice the size and weight of the O.S. .40, and it

ran like a Swiss watch. You could

almost just breath on it and it would start.

I

built the Cub with the clipped wing option.

It was a perfect second plane. Sticking

with the stability of the high-wing, but now with a semi-symmetrical airfoil and

clipped wing, I could still cruise pretty slow, but also have a plane that could

poke some holes in the sky and do some aerobatics.

I

built the Cub with the clipped wing option.

It was a perfect second plane. Sticking

with the stability of the high-wing, but now with a semi-symmetrical airfoil and

clipped wing, I could still cruise pretty slow, but also have a plane that could

poke some holes in the sky and do some aerobatics.

With

spring came the day to finally fly my new creation.

That day at my flying field, I went from joy to despair in the space of

about 3 minutes. Here’s how it

happened:

I

put in about a half tank of fuel, took off and flew the first flight without

incident. As a matter of fact, I

was thrilled with the way the plane flew and responded.

If the Goldberg Eagle was a Honda Civic, the clipped-wing Cub was a

Lexus. I smoothly circled the field

several times, getting the feel for my new baby, and setup and landed it within

a few yards of where I wanted it, just as smooth as can be.

I

put in about a half tank of fuel, took off and flew the first flight without

incident. As a matter of fact, I

was thrilled with the way the plane flew and responded.

If the Goldberg Eagle was a Honda Civic, the clipped-wing Cub was a

Lexus. I smoothly circled the field

several times, getting the feel for my new baby, and setup and landed it within

a few yards of where I wanted it, just as smooth as can be.

It’s

hard to describe the feeling, after spending the good part of a winter creating

this thing, to experience the success of such excellent performance on the first

flight. I thought of all the fun I was going to have flying this

plane in the future. Unfortunately,

in about 60 seconds, my Cub would be in 9 jagged, ugly pieces.

I

wanted to take it right up again, thought of adding fuel, and decided there was

at least enough for a short flight. I’ll

never forget this takeoff. I

throttled up and started my takeoff run with everything fine.

I rotated and started climbing out, and just then heard an engine

problem. The engine then sputtered

and died with the plane about 75 feet up, the worst place in the world to lose

your engine. I had to turn because

I didn’t have much field to work with. Had

I turned right, I may have been able to save the plane.

But I’ve always been more comfortable turning left, and in this

emergency situation, that’s what I did. They

say when you run out of altitude, airspeed, and luck at the same time, you’ve

crashed. My beautiful Cub

couldn’t turn around at that speed, stalled a wing, and crashed into a small

metal storage shed.

I

was in shock. I went to my plane

saying no, no, no…not believing what my eyes had seen just happen.

There it lay, the wing snapped in two, and the fuselage broken into 7

ugly pieces.

I

was in shock. I went to my plane

saying no, no, no…not believing what my eyes had seen just happen.

There it lay, the wing snapped in two, and the fuselage broken into 7

ugly pieces.

I

gathered up the pieces and sadly took them home, still in disbelief.

How could my engine fail me like that?

There was no reason for it to quit, unless it had no fuel.

But there was about ¼ tank of fuel left in the tank.

I

finally found the answer, which turned out to be an incredibly stupid mistake

that I had made in mounting the fuel tank.

Because

of the fueling setup I had added, the tank had fit in the plane better when mounted backwards,

and without thinking it through, I mounted it that way.

So the rear of the tank with the clunk fuel pickup was at the firewall. So what happened when the plane rotated nose up on takeoff?

As long as there was plenty of fuel in the tank, no problem….there was

still fuel up front. But when the fuel level went down to about ¼ tank, there was

no fuel in the front of the tank when the plane rotated, so naturally the engine

quit from fuel starvation.

Because

of the fueling setup I had added, the tank had fit in the plane better when mounted backwards,

and without thinking it through, I mounted it that way.

So the rear of the tank with the clunk fuel pickup was at the firewall. So what happened when the plane rotated nose up on takeoff?

As long as there was plenty of fuel in the tank, no problem….there was

still fuel up front. But when the fuel level went down to about ¼ tank, there was

no fuel in the front of the tank when the plane rotated, so naturally the engine

quit from fuel starvation.

As

embarrassing as it is to admit my pure stupidity, I do so because it shows that

you can’t really get away with stupid mistakes in this sport.

You will pay for them.

Not

only am I wiser about fuel systems, but now, before flying, I always pickup my

plane with the engine running, and tilt it up, down, sideways, and make sure the

engine runs well in all attitudes. If

it doesn’t, I don’t fly until I’ve figured out why.

To

make a long story even longer, I did a nice job of rebuilding the Cub, and had

more than 100 flights with it that year. I

got pretty good with it too, and by the end of the year I could fly circles

around the field with the plane inverted, as well as doing simple aerobatics.

To

make a long story even longer, I did a nice job of rebuilding the Cub, and had

more than 100 flights with it that year. I

got pretty good with it too, and by the end of the year I could fly circles

around the field with the plane inverted, as well as doing simple aerobatics.

I

was into flying quietly, so I had a quiet muffler on the Rossi and over-propped

it with a 12x8 APC. I flew at low

rpm and it was very quiet.

I

was into flying quietly, so I had a quiet muffler on the Rossi and over-propped

it with a 12x8 APC. I flew at low

rpm and it was very quiet.

My

next plane was a disaster. After

this one-flight wonder, I had to take an 8-year break from flying.

My

next plane was a disaster. After

this one-flight wonder, I had to take an 8-year break from flying.

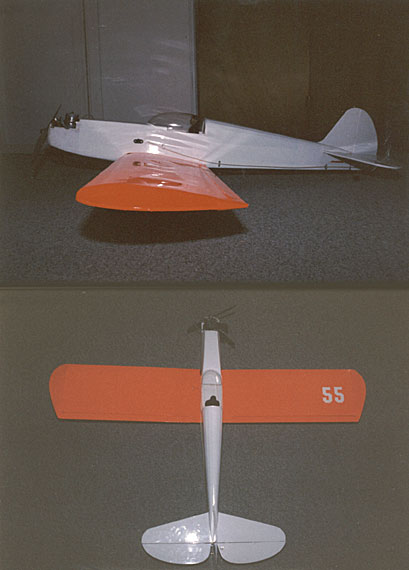

When

the Cub was pretty worn out from all the repairing and flying, I made the

decision to try a low-wing plane, and chose a Great Planes .40 Sportster.

This was a fully-symmetrical, low-wing plane with beautiful lines.

I spent a whole winter building the Sportster.

Although the Rossi engine was losing some of its power, I installed it,

with the same radio system, into the new plane.

You would think that with my level of experience in modeling / flying,

that I would have a clue about how to successfully build and fly a model

airplane kit. Not so.

The

control surfaces on the Sportster are not very large.

If I were setting this plane up today, I’d go for the maximum throw

(deflection) possible on all the control surfaces.

Back in 1991 when I built it, I didn’t have much deflection at all, but

it seemed to be pretty close to what the manual recommended, so I went with it.

I balanced the plane, got everything set up, and went to my field for the

first flight.

From

the moment it started flying, the Sportster felt wrong.

It seemed to need a lot more runway to takeoff, and when it finally did,

it seemed like it didn’t really want to fly.

I made my first turn and decided to just make a half circle and land

right away. The Rossi was running

but seemed weak, the plane was just hard to control, didn’t seem to want to do

what I asked it to do. When I

turned on final and cut throttle as usual, it went completely out of control,

fell out of the sky, and smashed nose-first into the tennis court, destroying

the fuselage.

From

the moment it started flying, the Sportster felt wrong.

It seemed to need a lot more runway to takeoff, and when it finally did,

it seemed like it didn’t really want to fly.

I made my first turn and decided to just make a half circle and land

right away. The Rossi was running

but seemed weak, the plane was just hard to control, didn’t seem to want to do

what I asked it to do. When I

turned on final and cut throttle as usual, it went completely out of control,

fell out of the sky, and smashed nose-first into the tennis court, destroying

the fuselage.

As

I drove home that day with my new Sportster in a trash bag, I guess I decided

that I had better things to do with my time than r/c flying.

Eight years later, I started again with the help of a gentle lady.

My son David and I built and flew two Goldberg Gentle Lady gliders for a couple of years before we got back in to powered models. He was getting some good stick time at the age of 10. We would hand-launch for each other and get 15-second flights. Sometimes the launcher would run after the Lady and try to catch her downfield. Later on, we got a high start and got some higher, longer flights. Once, I flew her right into a goalpost. David hit me in the leg with her once when trying to land. We’ve had a lot of fun with her, and we still use that old Futaba Attack AM radio system in the glider.

For

our new start in powered flight we have two beautiful SIGs: a Kadet LT-40 w/TT

.46 Pro, and a SIG Kadet Senior

w/ TT .61 Pro.

This

is a shot of my big brother Dave, hand-launching the Goldberg Eagle 63 on his

farm in West Virginia. He was nice enough to retrieve it from a tree that

day. (Not the tree in the picture, I managed to avoid that one)

This

is a shot of my big brother Dave, hand-launching the Goldberg Eagle 63 on his

farm in West Virginia. He was nice enough to retrieve it from a tree that

day. (Not the tree in the picture, I managed to avoid that one)